(Holy) Trinity Anglican, South Australia's oldest church, opens in 1838 at Town Acre 9 provided on North Terrace, Adelaide

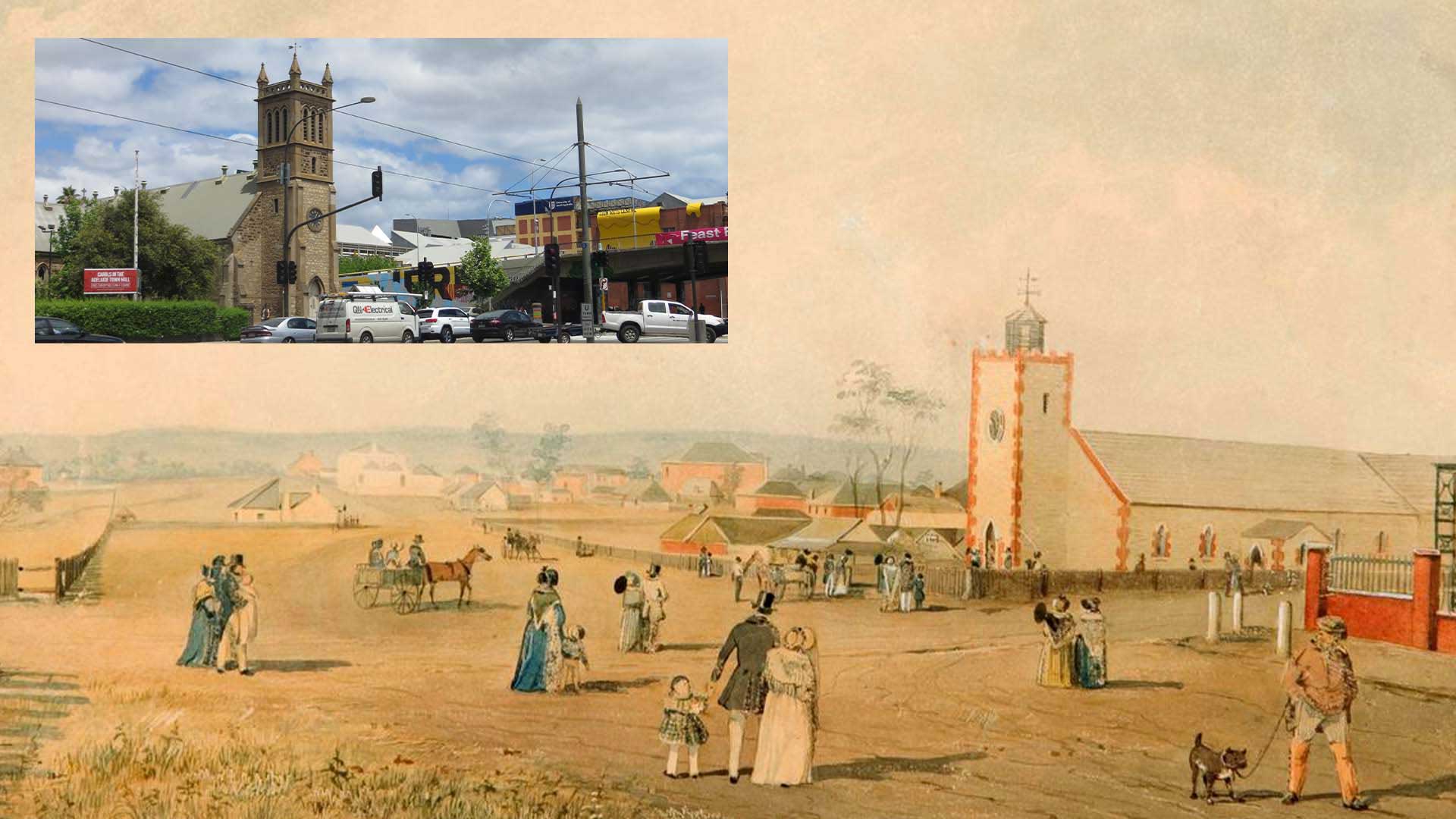

S.T. Gill's watercolour from 1845 of Trinity Church on the corner of North Terrace and Morphett Street, Adelaide city. Inset: The 21st Century Holy Trinity church with architect E.J. Woods' additions.

Main image courtesy Art Gallery of South Australia

The Anglican Holy Trinity (originally called Trinity) on North Terrace, Adelaide city, became the oldest surviving church in South Australia. Although rebuilt in 1880s to architect E. John Woods’ design, it retained original elements from 1838.

Before official European settlement in 1836, the South Australian Church Society was formed in England to assist colonists’ public worship in “the doctrine of the Church of England (Anglicanism)”. South Australia was founded on radical principles of religious equality between Anglicans and non Anglicans. Unlike in Britain, only minimal state support was provided to the Anglican church, with an Anglican colonial chaplain appointed.

The first chaplain was Charles Howard, who arrived with first South Australian governor John Hindmarsh on the HMS Buffalo in December 1836. Howard was Irish from the church’s evangelical wing. Evangelicals, well represented among early Anglican clergy, eventually became a small minority. As colonial chaplain, Howard was expected to conduct marriages and burials for anyone and, until 1840, he was the colony's only Anglican clergyman. The costs and worries of the early church and ministering to a widely dispersed congregation contributed to his early death in 1843. James Farrell, first dean of Adelaide, then became the incumbent of Trinity Church, also marrying Howard's widow, Grace.

After the survey of the City of Adelaide in March 1837, a town acre donated to erect an Anglican church and parsonage was given priority. Surveyor-general William Light selected Town Acre 9 on North Terrace. There, it was proposed to erect prefabricated structures dispatched from England with Howard. But in July 1838, a South Australian Gazette and Colonial Register article noted that “the only part of the wooden church that exists … is a strange sort of extinguisher, dignified, we believe, as the steeple. The other portions did not fit, or were not supplied, or were splintered or rotten. It was found impossible, in short, to put the rubbish sent out together, and a stone building has been erected by subscription.”

The foundation stone for that building was laid by governor Hindmarsh on January 26, 1838. John White completed construction by August. The church became such an important landmark that a clock made by Benjamin Lewis Vuillamy, clockmaker to King William IV, was installed in its tower. So many people applied for pews that the church was enlarged in 1839. In 1844, it was declared unsafe, closed for repairs, and partially rebuilt by R.G. Bowen. A stained-glass window dated 1836 and bearing the monarch’s name, “W IV R” (King William IV), was only relic of the original prefabricated building, while the tower and lower nave walls were kept from the first stone building.

The church reopened in 1845. When the first Anglican bishop Augustus Short arrived in 1847, Trinity was dignified as cathedral church pro tem. Many pioneer clergy were ordained there by Short and, in the 1840s, the church attracted large congregations including the Anglican governors and other “principal persons of the colony”. James Hurtle Fisher, South Australia’s first resident commissioner and first mayor of Adelaide, was a trustee of (Holy) Trinity Church. It was also the military’s church. In the 1880s, architect E. John Woods designed alterations carried out by the builder Codd.

Anglicans were an early majority of the South Australian population but, from the 1870s, their proportion was lower than elsewhere in Australia. Among regular churchgoers, especially in rural districts, Anglicans were always outnumbered by Methodists. This strongly Protestant environment prompted the Anglicans to emphasise their difference in teaching and worship. The Anglicans tended to go “high” – with more mystic ritual of the established Anglo-Catholic church – rather than "low".